Ida B. Wells-Barnett totally bit a train conductor and then turned around and sued the railroad.

This month marks the marked the 105th anniversary of the March, 1913 suffrage parade in Washington staged to coincide with Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. To mark the 100th occasion of this occurrence, many woman’s groups gathered in Washington (in 2013) to recreate this parade and celebrate how far women have come since the original march. Nice, right? Did you know the original organizers of the march wanted the Black women to march in the back?

Let’s take a closer look, without the rose-colored glasses. Woman’s suffrage was not for all women. The National American Woman’s Suffrage Association, in order to play nice with southern women, requested the black women march in the back of the parade rather than with their state delegations. Remember now, the very point of the march was to promote EQUALITY. Hmmmm. Anyone else see a problem here?

Let’s take a closer look, without the rose-colored glasses. Woman’s suffrage was not for all women. The National American Woman’s Suffrage Association, in order to play nice with southern women, requested the black women march in the back of the parade rather than with their state delegations. Remember now, the very point of the march was to promote EQUALITY. Hmmmm. Anyone else see a problem here?

Mary Church Terrell, another leader of the Black woman’s suffrage movement, agreed to “make nice”. She was willing to sacrifice the mission of the Black women fighting the battle on two fronts: sexism, and racism in order to pacify the “big names” in the woman’s movement. Certainly her reasoning was sound in some ways. I’m sure she thought if the feminist battle was won, then the white women would fight against racism. However, given that the very feminists she wanted to fight for black women later, refused to fight for them now makes me think her reasoning was a little off.

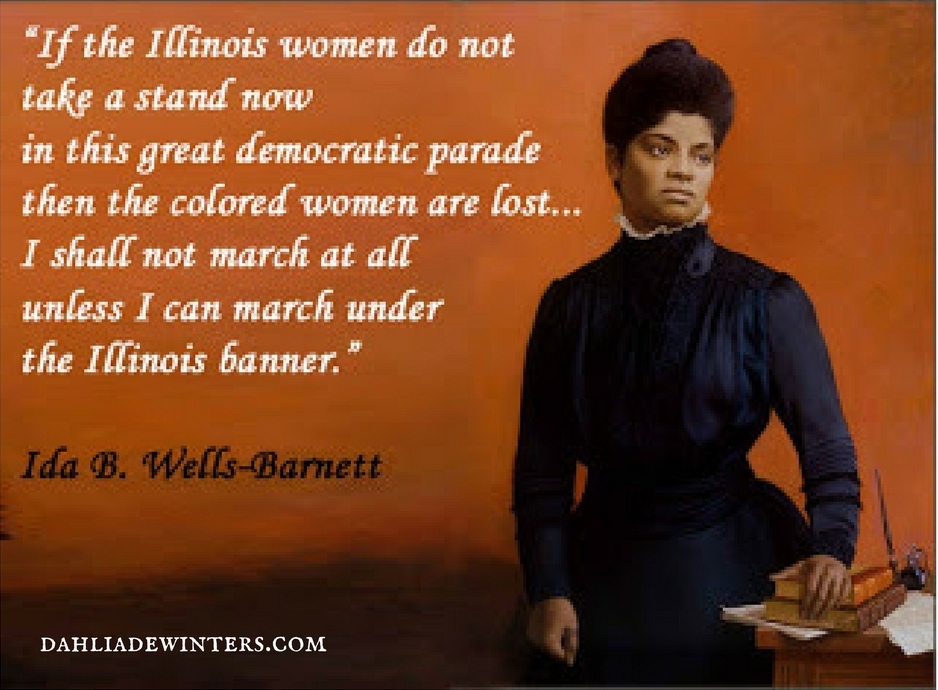

There was another woman who disagreed with Mary Church Terrell’s stance: Ida B. Wells-Barnett. She once bit a train conductor who tried to forcibly remove her from a train car after she refused to leave the ladies’ car for a smoker car. This was a woman who had written several pamphlets condemning the practice of lynching and lived with death threats from whites. Of all women, she was not going to pander to the wishes of a racist South.

Refusing to conform to the designated black ranks, she “hid out” until her delegation had passed, then surged into the group of white women — some hostile, some not — and took her rightful place in the Illinois group. According to the timeline on the site http://idabwells.org, her actions began the integration of the movement. She also had to be protected from the other women in the delegation who were, ah, slightly peeved that an (uppity) Negro woman dared march among their ranks, after she had been explicitly told not to.

Now that’s bravery.

It is unfortunate that Mrs. Wells-Barnett isn’t a more prominent figure in history, especially in the context of women’s suffrage and the civil rights movement. Mind you, many of the websites that give biographies of Mrs. Wells-Barnett either gloss over the march, or don’t mention it at all. However, a bit of research can reveal how forward thinking and courageous this woman really was, to take on men (black and white) AND white women.

Check out the little story I wrote about the suffrage parade here.

Further Reading:

Ida B. Wells: Civil Rights Activist

When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America

Ida B. Wells: Crusade for Justice

Ida B. Wells Memorial Foundation